Words by Deborah Findlater

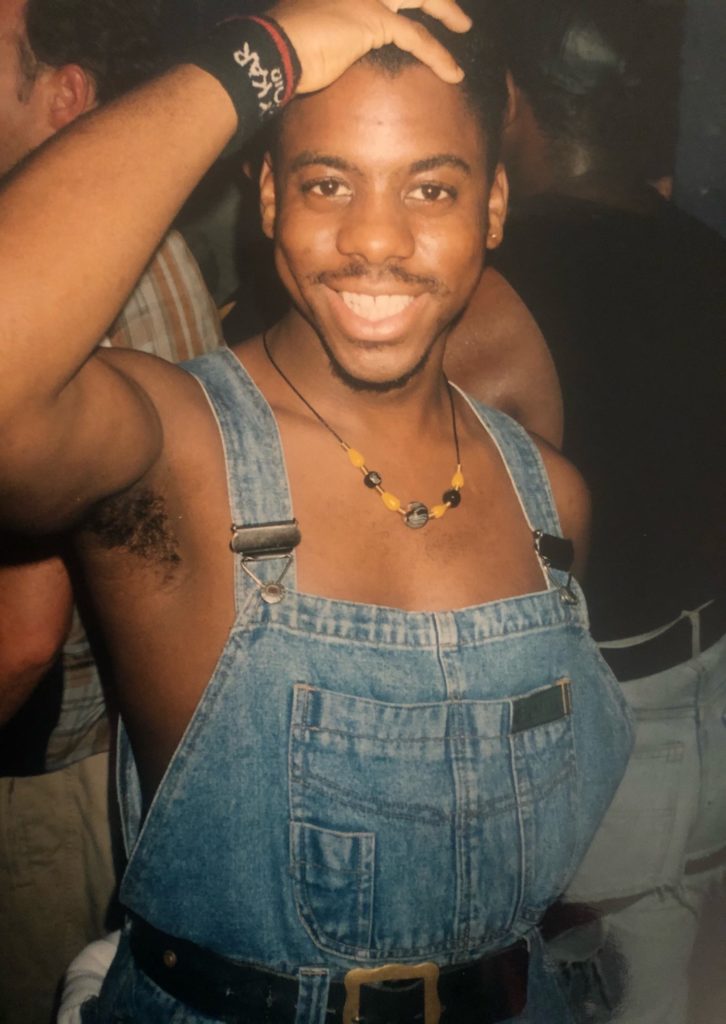

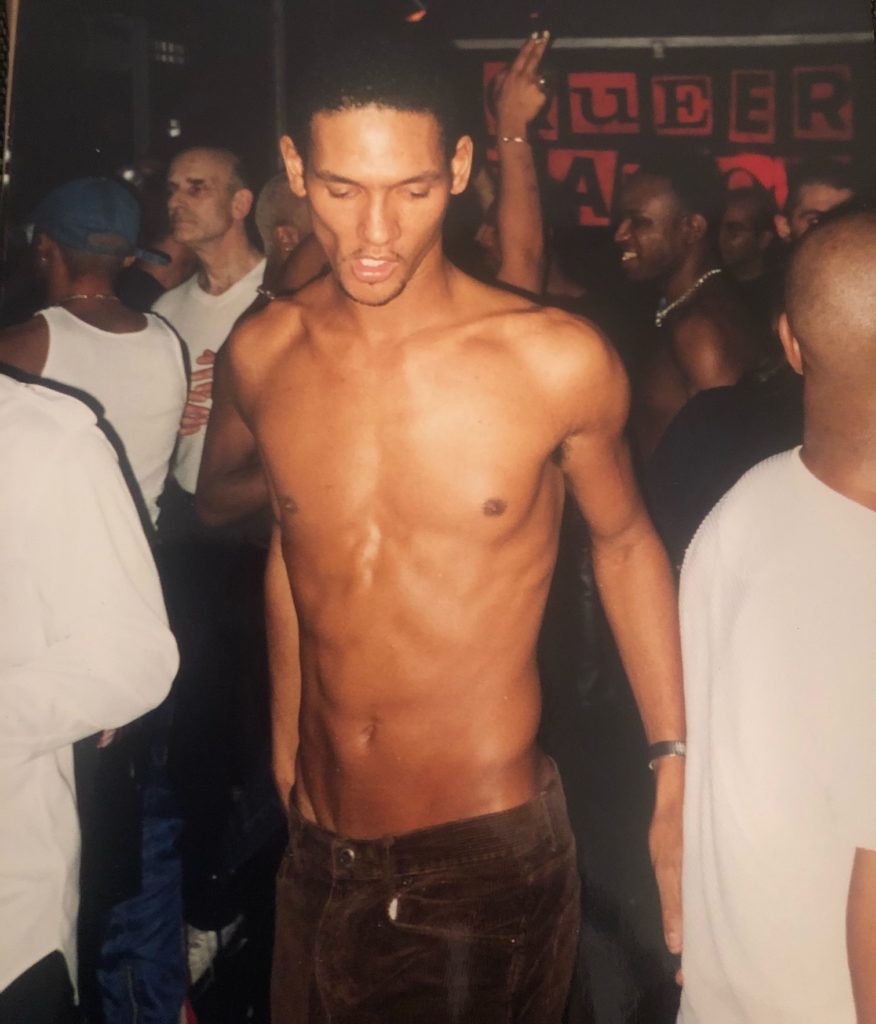

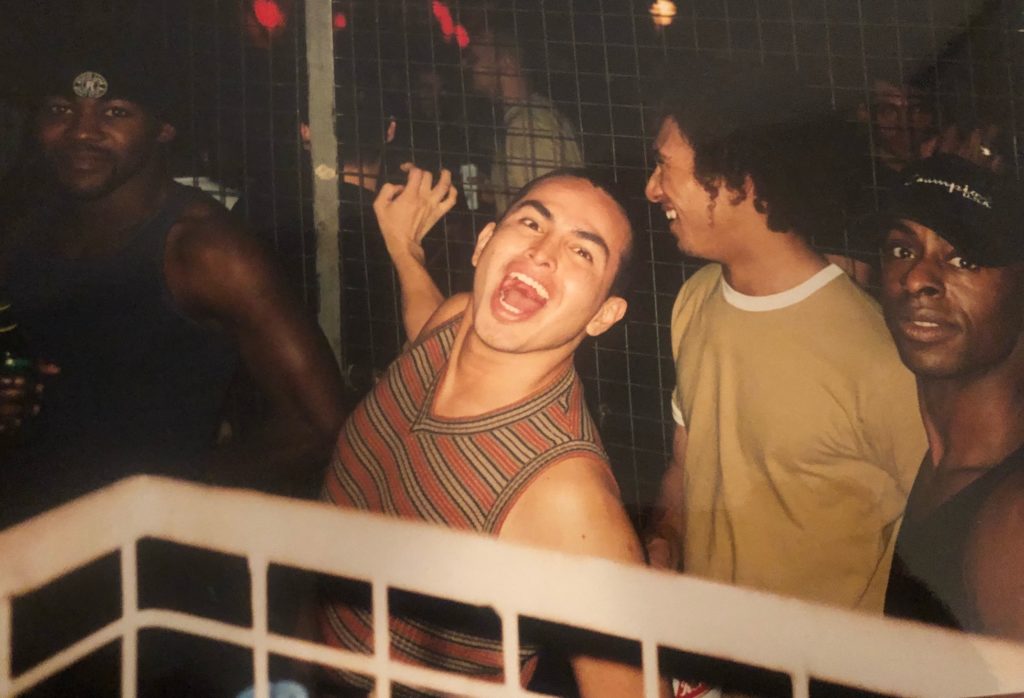

All photos by Luke Howard

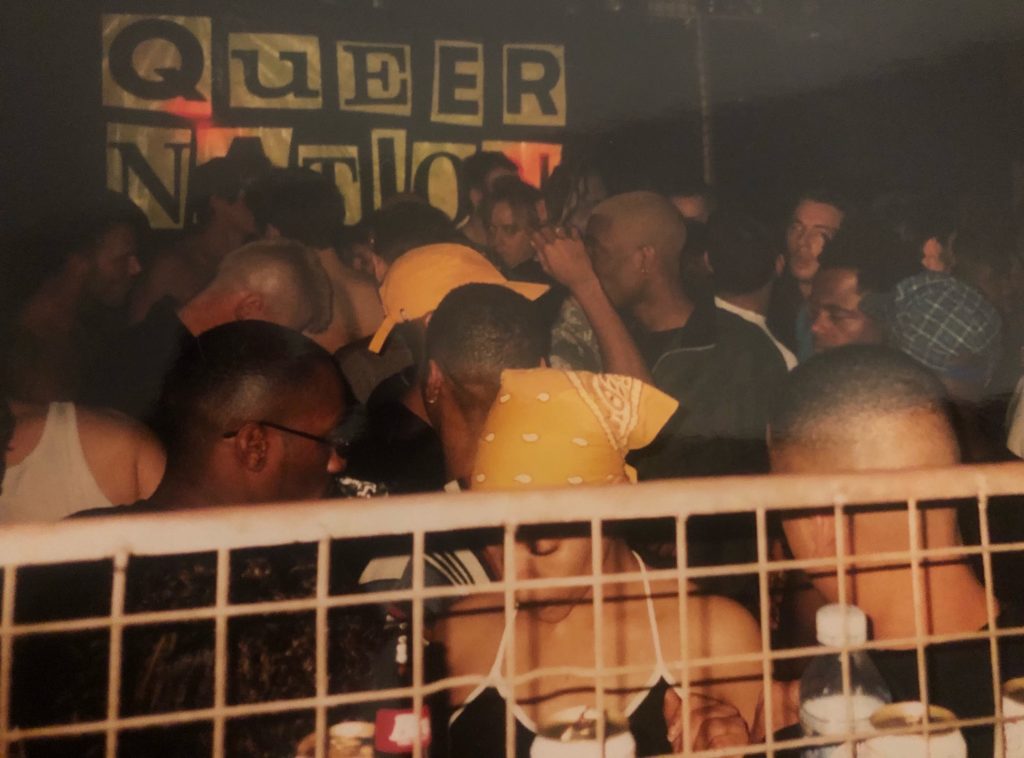

Moving together, breathing together, being together. All things many of us have missed in a year of club and rave closures. The importance of such, particularly for Black queer folks, is acutely felt; whether for wellbeing, income, community and much more. Although venue closures and the ever-expanding monster of gentrification have had an impact, London still remains home to a thriving Black queer nightlife scene with parties such as: Queer Bruk, Bootylicious, Let’s Have a Kiki, Nite Dykez and Faggamuffin; and collectives like Black Obsidian Soundsystem and BBZ, alongside a host of DJ’s playing at club nights across the city, notably Femmi-erect, 079me and Pxssy Palace. This stems from a rich legacy laid down by nights such as Precious Brown, Blessence, Liberté and Queer Nation, as recalled by DJ and sound artist, Ain Bailey, and artist, archivist and community organiser Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski. In this pivotal moment of breaking down harmful structures and coming together to build a more equitable future, what seeds have been planted that point us towards a better way of being? Through interviews with a selection of the Black DJ’s and ravers present at the parties, we reflect on seminal London club night Queer Nation and its impact.

It was through a trip to San Francisco that founder Patrick Lilley came up with the name Queer Nation, after the infamous LGBTQ activist group. First founded in March 1990 in New York City by a group of activists who were also part of HIV/AIDS advocacy organisation, ACT UP, branches soon spread across the U.S. including to where Lilley visited friends who told him of the organisation. Due to the reclamation of a term that was still widely seen as derogatory and their direct-action tactics, Queer Nation caused a necessary stir in light of increasing homophobic violence. One particular action the San Francisco chapter undertook was a Halloween protest against two visiting fundamental Christian ministers who intended to carry out an ‘exorcism’ in the city, even forming the wittily named focus group, GHOST (Grand Homosexual Outrage at Sickening Televangelists). Inspired by this D.I.Y. punk approach, Lilley created the logo for the club night in a similar Xerox style.

As well as the attitude, Lilley was influenced by another product from the States: the music. House formed the musical foundation of Queer Nation, something greatly intentional given how impacted Lilley had been by the renowned Paradise Garage in NYC with artists like Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan. Previously in the late 1980’s, Lilley had run the club High on Hope in Camden with DJ Norman Jay focusing on a sound geared more towards soul, featuring prestigious guests such as Chaka Khan, Loleatta Holloway, Gwen Guthrie and En Vogue. The increase in tempo that came with 90’s led to a new stage in the evolution of house music and required a new, explicitly queer space to accommodate it.

Opening in December 1990, Queer Nation first begun its life at The Gardening Club, Covent Garden. For the next 7 years it held down a regular Sunday night spot amassing a legion of loyal attendees. The Sunday session has all but ceased to exist in London with clubs like Plastic People closing, however it offered a unique experience and space. After it moved to a Saturday night, taking place at a variety clubs notably Substation South in Brixton, Union and Barcode both in Vauxhall up until 2018 giving it an impressive 28-year lifespan. During this time resident DJ’s Princess Julia, Supadon, Luke Howard and Jeffrey Hinton became infamous for consistently setting the musical tone of the night and maintaining its unique character. Its duration is one of the many reasons why it stands out as special. From it being a rare Queer night that centred on soulful house, to it drawing in renowned DJ’s and artists such as Little Louie Vega and Ultra Nate to many attendees finding lifelong friends, Queer Nation holds an iconic legacy. Creating a space that was intimate yet an experience that was expansive it deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

We speak to DJ Paulette, Robert Shaw and Paul McLennon, who were all part of the Queer Nation community, gathering their cherished memories and experiences of the night.

DJ Paulette first attended Queer Nation in 1994 after moving down to London from Manchester. Having known original line up DJ, Princess Julia from their time playing at the iconic Hacienda, their relationship deepened as well as with Luke Howard and Patrick Lilley, resulting in DJ Paulette playing the party herself a few years later. As both a raver and a DJ, she offers a unique perspective on the night.

DJ Paulette: Queer Nation was about Black music. Songs, voices and dancing. It was about the dance floor. The uplifting vibe and environment.

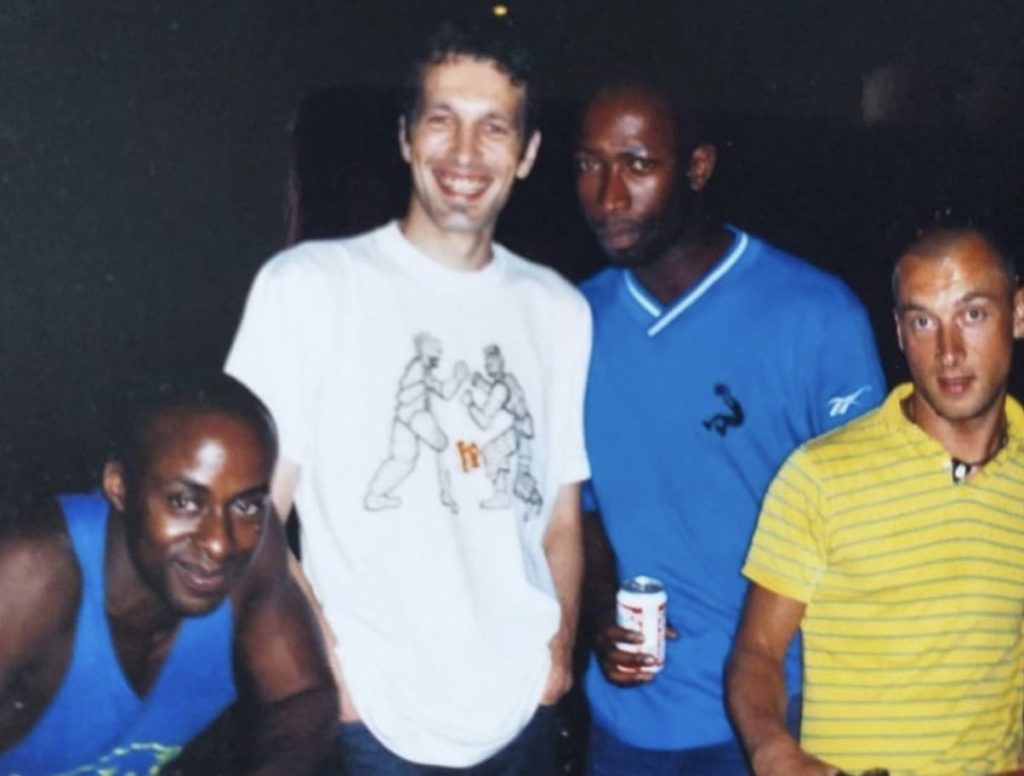

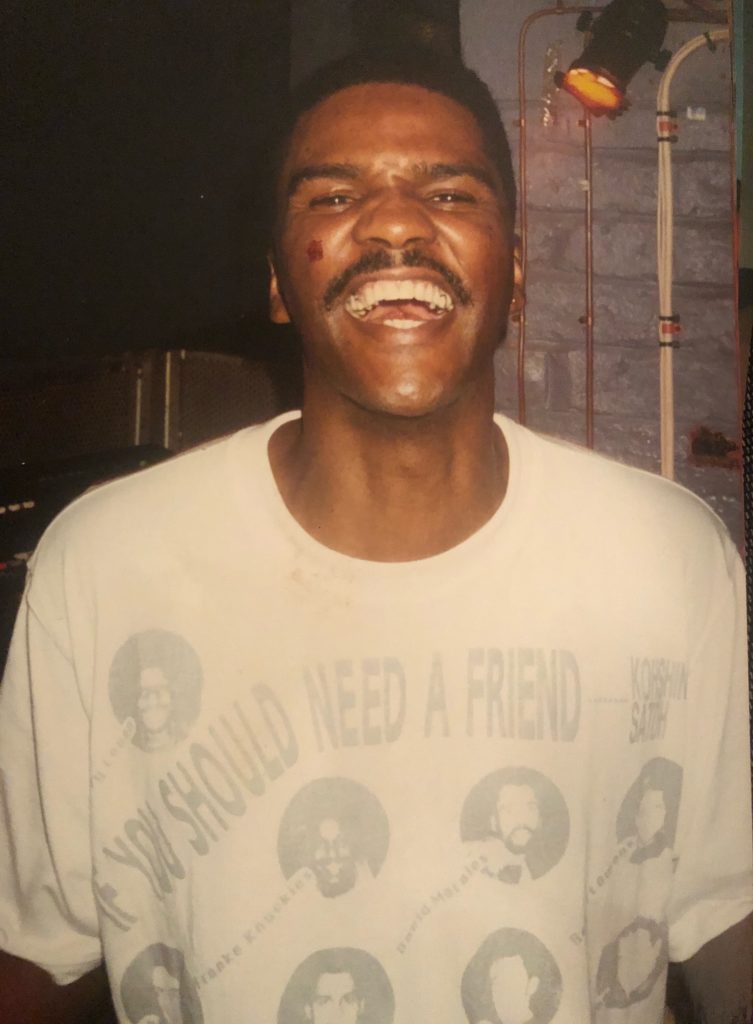

Photo was taken with a phone provided by Paul Allard.

In order of appearance: Elliot Pinkett, DJ Harvey, Paul McLennon, Paul Allard

Deborah: I’m really just thinking about how it originally was on a Sunday, and just how spiritual house is.

DJ Paulette: Totally. I feel like that about house because a lot of the house music that you listen to is gospel. Listen to the lyrics and they’re coming from gospel. You know, the singers, whether it’s Bebe and Cece Winans or Michael Procter, Michael Watford, even Barbara Tucker, Jocelyn Brown, they’re all church singers, and they’re bringing that kind of spiritual experience to play with their lyrics and their songs and their vocal delivery for house music. Sharon Pass who worked with J.M. Silk. All the original house. Frankie Knuckles, Robert Owens and Darryl D’Bonneau, singers like that. It was like mixing gospel church with house and so doing it on this Sunday was definitely that kind of religious experience without the church.

Deborah: I feel like the club is often a space for Black and queer people to experience that kind of congregation. And it’s a very transcendental experience. It’s very much like you’re purging as well.

DJ Paulette: Totally! That’s dancing, the sweat, the purge, the expression, the release, the tension and release. You can watch black people dancing, like properly dancing to house music and there will be a point where you will raise your hands. It’s like, am I receiving or am I releasing? Because in that position, you’ve got the two ways you’re open, even just in like spiritual terms, like you said, transcendental. You’re open. Your crown is open. Elevation- by Blaze, if you go listen to that song and he’s saying the beauty of Elevation is that you can literally fly above the galaxy. I think they even had Blaze play at Queer Nation as well as Josh Milan and Kevin Hedges. That was the ilk of the DJ’s that were playing.

Deborah: I’m really struck by the feeling of it because obviously in this period of time where we can’t rave, you realise how vital it is for your nourishment as a person. How did you feel afterwards? Like going into the week? Because it was a weekly night

DJ Paulette: Yeah, it was every Sunday. Because of licencing being different anyway, your Sunday clubbing always finishes by midnight and it never goes on super, super late, so you can be at work on Monday morning no problem. I don’t go to church. I’m not a church person. I have my own church. Music is very much my thing. Whenever I went to Queer Nation and then later it was Lazy Dog or Faith or Sunday Sonic or one of those Sunday clubs for soulful house music, I always felt like I had this big release and sometimes a revelation if I’ve heard this new tune and I’ve got down and I’ve surprised myself with a move or a jump or spin or something, and I’ve gone like, yeah! I actually did get into it so deep that I lost myself for a moment in the music. And I love that. And I really did feel Sunday clubbing and Queer Nation set me up for the week.

Deborah: It’s so good to talk about dancing and congregation and movement with you, because I feel like that space is so essential for us as Black people because, Monday to Friday, you’re going through whatever you’re going through, you’re in work etc. and you need this release, this receiving. With phones and social media, we’re in our heads a lot but nothing beats movement and what you can actually do with your body in a space.

DJ Paulette: Going through lockdown and I’m kind of looking at my body, how it’s changed in the last few months and I’m wondering why it’s changed then I thought it’s because I’m not dancing. And dancing is key, and that brings it back very nicely to the Queer Nation experience, because dancing was the centrepin. I used to really always enjoy connecting with anybody on that dance floor that could match my steps and that could do better because it always encourages you to do better, to go further. It’s a whole other conversation when you start to dance with somebody, it’s a whole way of communicating. [As a DJ] I’d spend the week going through records, thinking what will have the best and most desired effect. It’d generally be the records – I always had my two best Queer Nation clubbing friends, Sean and Alex in my head – that would make them jump. We had a way of being very coordinated on the dancefloor.

Deborah: Dancing like that is very call and response, referring back to the church

Robert Shaw is a long standing friend of DJ Paulette, having met at seminal gay night Flesh at the Hacienda. As a raver and regular attendee across venues, he holds the night close to his heart, having a number of memorable experiences of it.

Deborah: What made Queer Nation stand out as a club night for you?

Robert: The music! The DJ’s really knew their stuff and the music was excellent every time. I can’t think of another gay club that was playing the same genre of house music they played as other clubs tended to play much harder house. Even when the Queer Nation DJ’s played at other venues their music changed which for me made Queer Nation more special and unique. I had so many good nights, the music, the crowd all helped to keep it special for as long as it was.

Deborah: Why was it so important to you and the other Black ravers?

Robert: I think Queer Nation became more important to Black ravers when it went to Substation South from the Gardening Club in Convent Garden. When it was at the Gardening Club it was on a Sunday night, and my recollection was the audience wasn’t predominately Black. This changed when it moved to Substation South, as it was on a Saturday in Brixton before the area became gentrified, so it was easy to access for many Black ravers who lived in or close to the area. If truth be told, Substation South was a dive, but it was unpretentious which set it apart from some of the other clubs at the time, especially those in the west end. There was also Black door staff which helped Black ravers feel more welcome than other clubs.

For Paul McLennon a friend of one of the party’s resident DJs, his Queer Nation journey began in 90/91. Despite not living in London at the time, the night would be an absolute must on weekend visits.

Paul: It was a whole kind of new experience for me. It was a small intimate space and it was populated by people who really loved the music. A really fabulous, all-inclusive sound. They were more interested in pushing forward that community spirit and just wanted people to have a great time. I have made friends who I’m still in contact with. It was a fresh outlook, a way to drive into the week and give you some kind of inspiration. Yeah, inspirational. The night was inspirational. That’s the word!

Deborah: Is there anything that you think from that time people could take forward for queer nights?

Paul: Just a spirit of being together and oneness, looking out for your fellow human beings. And being gracious to whoever’s around you and realising that people are actually suffering and kind of trying to bring them up.

Deborah Findlater is an artist, filmmaker, writer and DJ from London. Her work explores issues surrounding working class Blackness in Britain, Black Womxnhood and queerness. Under her DJ moniker, Pepper Coast, she is committed to playing dance, electronic, bass & drum heavy sounds from across the African diaspora. She is a part of London based QTIBPOC soundsystem and collective Black Obsidian Soundsystem (B.O.S.S.).